It wasn’t just a new number that came with Big Sur, finally turning macOS from 10.x to 11, but a new way of thinking about the difference between system files and your own data. In the past, many of us had bootable external drives, regularly updated, that we could use to start up our Macs in a pinch, such as when we had a drive failure or some kind of corruption or other problem that required wiping a disk altogether. We might boot from the drive to keep on working, or use the files on the drive to restore our Mac quickly—a fast copy instead of a system reinstallation.

But it’s a new world: Big Sur resists the ideas of a bootable external backup, though more particularly it resists easily updating an external copy of your startup volume’s system files. In this Mac 911 column, let’s start with an explanation of why that is, so you understand exactly how difficult the task has become, and then proceed to the best new strategy.

Apple splits the startup volume into two pieces

Apple phased in the process of changing how it organizes the startup volume through a phase in of the APFS (Apple File System). APFS first became mandatory for SSD-based Macs and then for ones with a Fusion drive. APFS allowed more a sophisticated organization of aspects of macOS in the startup volume’s partition. Along the way, Apple kept adding more features to APFS.

This culminated in macOS 10.15 Catalina in splitting macOS into two pieces, which appear seamlessly as a single unit in the Finder, but which severed a long-time intermingling of files. With the concept of a volume group in APFS, Catalina organized all system files and core apps into one volume and all user-owned and user-modifiable data, third-party apps, and some Apple apps into another. The system volume is read-only and locked against modification during an active macOS session; the Data volume can be read and written, and apps on its may be launched. (The Big Sur volume isn’t even mounted directly, but as a read-only APFS snapshot, making it even harder for an attacker to find a way in.)

Big Sur took that one step further in a way that affects your ability to continue to make backups of the style you might be accustomed to, and which requires a rethink for the present and future. Big Sur picked up on the system/Data volume division of Catalina, but added another layer: when installed or upgraded, macOS’s system volume has a cryptographic wrapper around it that prevents the slighest modification without detection.

https://www.macworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/mac911-apfs-volume-group.png?resize=300%2C279&quality=50&strip=all 300w, https://www.macworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/mac911-apfs-volume-group.png?resize=768%2C715&quality=50&strip=all 768w, https://www.macworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/mac911-apfs-volume-group.png?resize=1200%2C1118&quality=50&strip=all 1200w, https://www.macworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/mac911-apfs-volume-group.png?resize=1536%2C1431&quality=50&strip=all 1536w, https://www.macworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/mac911-apfs-volume-group.png?resize=2048%2C1908&quality=50&strip=all 2048w" sizes="(max-width: 2538px) 100vw, 2538px" />

https://www.macworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/mac911-apfs-volume-group.png?resize=300%2C279&quality=50&strip=all 300w, https://www.macworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/mac911-apfs-volume-group.png?resize=768%2C715&quality=50&strip=all 768w, https://www.macworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/mac911-apfs-volume-group.png?resize=1200%2C1118&quality=50&strip=all 1200w, https://www.macworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/mac911-apfs-volume-group.png?resize=1536%2C1431&quality=50&strip=all 1536w, https://www.macworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/mac911-apfs-volume-group.png?resize=2048%2C1908&quality=50&strip=all 2048w" sizes="(max-width: 2538px) 100vw, 2538px" />Apple calls this a Sealed System Volume, and it’s another layer of protection against both malware and other attempts to subvert your system to spy on you, corrupt your data, or exfiltrate personal information. But it’s not designed to be backed up in the way that macOS 10.14 and earlier were, and even how Shirt Pocket (SuperDuper) and Bombich Software (Carbon Copy Cloner) managed to get full Catalina backups working, too.

Essentially, a Big Sur system volume has to be installed on a freshly erased disk, because the process of making the seal is unique to each volume. Any change to even a single bit in the volume causes validation to fail (breaking the “seal”). Apple offers a bypass that Carbon Copy Cloner has managed to take advantage of, which is a low-level copying tool called asr that can in some (but not all) circumstances copy Big Sur’s system volume from an internal to an external drive and keep it in bootable shape. However, the folks at Bombich include a long list of provisos about what might go wrong during copying.

Even after making a valid bootable system copy, keeping it up to date is problematic:

- You can’t apply changes to the system volume. You either have to erase the drive and copy everything again, or boot with the external startup volume and perform a software update within an active Big Sur session.

- Updates to the Data volume on your internal drive when copied to the external could actually cause changes that prevent that external drive from starting up your Mac successfully.

(You can still opt to use an external drive as your main startup volume in Big Sur, just as with previous macOS releases. I switched my iMac from its slow internal Fusion drive to an external SSD months ago and then upgraded it to Big Sur and performed subsequent macOS updates without a problem. However, it’s my primary startup drive, not a backup.)

Bombich argues, as does Howard Oakley of the invaluable technical resource site Eclectic Light and Adam Engst of TidBITS, that it’s time for those of us interested only in being able to restore our Macs, not boot from an external drive, to give up on worrying about having a copy of the system volume on hand at all.

Back up the Data drive and don’t worry about the system

In this new way of doing things, your Data volume in the volume group is paramount. This makes sense: all the files in the system volume are immutable once installed and sealed into the volume. There’s no variability in them after you install or upgrade macOS. (If you don’t have a speedy internet connection or would prefer to always have a system installer on hand, you can make a bootable Big Sur installer; we provide instructions.)

You have a lot of choices for making an exact copy of your Data volume and keeping it up to date:

- Time Machine: Apple naturally continues to update Time Machine with each release of macOS, and after the first full backup of your Mac to Time Machine, you have a complete copy of your Data volume.

- Disk Utility: Disk Utility allows selection of the Data volume so it can be copied to a disk image or backed up as a separate volume on a drive.

- Carbon Copy Cloner: Carbon Copy Cloner has deprecated full drive clones in Big Sur of the sort described above, and its default “standard” mode creates a full clone of the Data volume, which it can upgrade incrementally. (Like Time Machine, it uses an APFS feature for snapshots, allowing a quick rollback, too.)

- ChronoSync: The synchronization and cloning software ChronoSync from Econ Technologies is adept at keeping files and folders in sync across many targets—folders, volumes, SFTP servers, cloud servers, etc.—but it can also create clones and archives of the Data volume.

(The long-running SuperDuper from Shirt Pocket is close to releasing a Big Sur-compatible update that’s free to existing registered users.)

When you hit a bump in the road and have to erase your startup volume, have your Mac or its drive replaced, or are migrating to a new Mac, you can restore through multiple options, too:

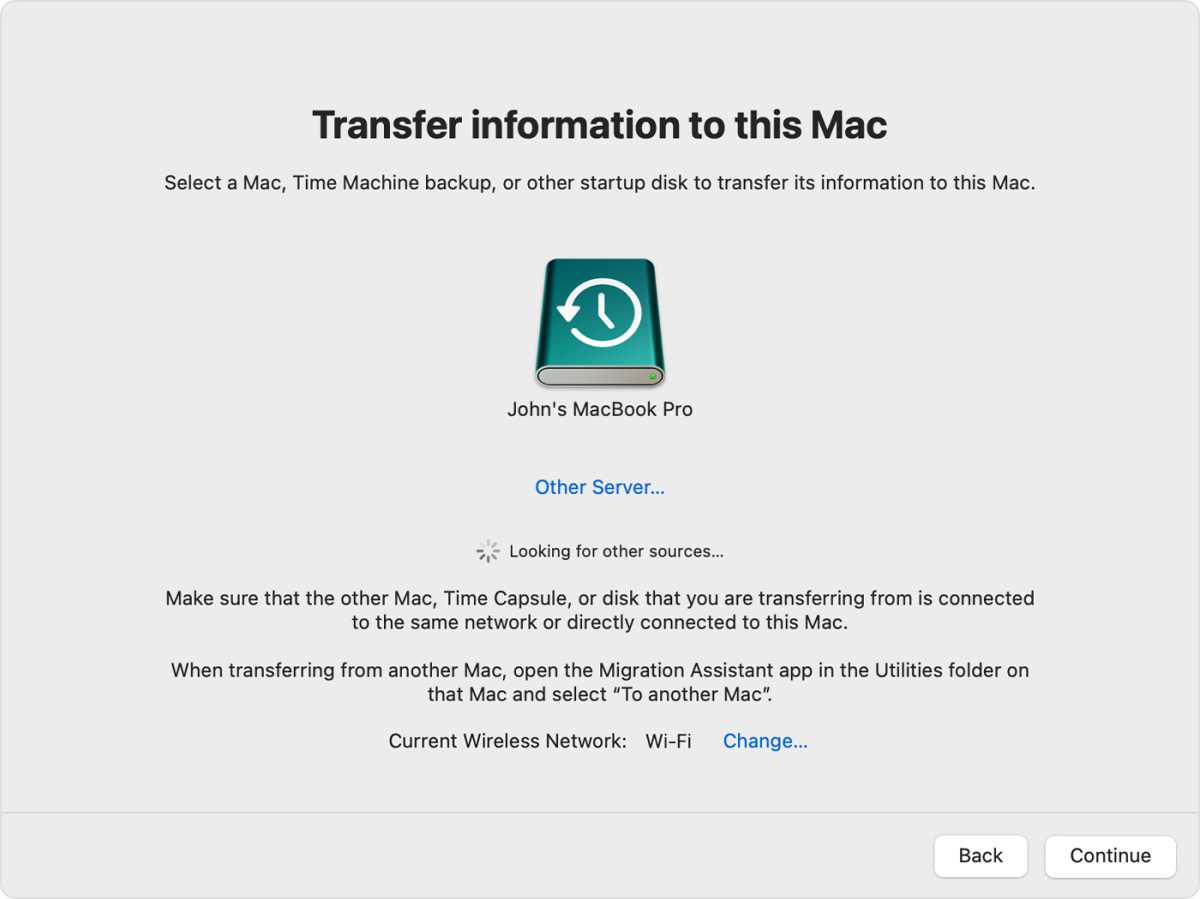

- Migration Assistant: With a freshly installed copy of macOS on an erased drive or on a new Mac, you can choose a Time Machine backup to restore the Data volume.

- recoveryOS: If the Mac has a working copy of recoveryOS—which it should after a fresh install or on a new Mac—you can instead start up into recoveryOS and restore from Time Machine there. (On an Intel Mac: choose > Restart and hold down Command-R until macOS Recovery appears. On an Apple silicon Mac: choose > Shut Down. When powered down, press and hold the power button until the startup options screen appears and click Options to authenticate and proceed to the macOS Recovery screen.)

- Disk Utility: Via recoveryOS, you can also use Disk Utility to restore the Data volume from any mountable volume or from a disk image stored on a mountable volume. Such a volume can be created by Disk Utility, Carbon Copy Cloner, or ChronoSync. After following the steps just above to reboot into recoveryOS and reach macOS Recovery, choose Utilities > Disk Utility. Apple provides instructions.

I know the security blanket of having a fully bootable external drive has meant a lot to many of us in the past, sometimes meaning the difference between getting back to work right away in the event of an internal drive problem and it taking hours to days. But Apple’s made the process of getting a Mac back into order so much simpler that for most of us, it’s time to make the backup change.